Searching for Truth

I've found myself recently, again, searching for a grounding narrative in a life and a world that feels altogether untethered, unpredictable and unreliable.

The grounding narratives that bolstered my youth have grown pale and unsteady in mid-adulthood, cresting the middle of my 30s with a mortgage, car payments, student loans, credit cards, marriage and kids.

My belief in my own irrepressible spirit and work ethic, and its desire to overcome inherently unjust institutional structures, has been replaced by a resigned and sometimes bitter cynicism, even while it is at the same time layered with a sense of unexamined guilt and privilege, when in comparison with some I have so little, and in comparison with many I have so much, too much.

As a person who desires to follow Jesus, my ultimate grounding narrative comes from the Bible: most importantly its Gospel story of Jesus himself, God Incarnate who lived, died, and rose again for the sake of global redemption. This narrative is layered in human sin and frailty, war and bloodshed, and even in the Bible's holiness humanity slips in, errant passages like cruise missiles zoom in and explode in duplicitous human interpretation; for generations this grounding text and our selfish interpretation has enabled communities to sanction abuse and oppression of the least of these.

Still, I writhe - and write. In a flurry of news reports and stolen passages sneaked while walking to the bus stop and wiping up crumbs, I sense the obliteration of the grounding American cultural Christian narrative. Evangelicals have succeeded in evangelization of power and wealth, particularly that of white men. We use words like Evangelical, which for the Apostle Paul was a verb meaning to share the story of Jesus, to describe an American cultural phenomenon that has little to do with the Middle Eastern Savior who bears the name Jesus.

As the cultural narrative risks obliteration, the "good guys" and the "bad guys" all switch roles and trust plummets. Mirages are destroyed and tyrants are exposed, while faith itself hangs in the balance. What's left of our American Christian faith has been replaced by spreadsheets and 401Ks and guns and storage cellars. Preservation and resignation pervade the echoey walls and windows of empty sanctuaries.

In God We Trust.

For years Americans have debated the wrong word in that saying, for our challenge of the moment is not with God but with Trust. As I write this the leaves blow off the trees and skitter faster down the muddy street, the newly melted first snow. I cannot grasp the life they shed so quickly, so easily, sacrificing themselves for new buds who are months away. Will they ever grow again?

Life has always demanded trust, but trust is also irretrievably human. It exists in a handshake, a nod, eyes meeting eyes and promising mutual regard.

Yesterday I got a phone call - several phone calls in fact - saying that my social security number had been breached and I had better fix it. The 1-800 number sometimes even matched that of the Social Security Administration.

I hung up.

I googled "social security number scam," and I learned it was a scheme - like others - of someone pretending to be someone else. An elaborate ruse, but one that required no response. I rejected the calls again and again, the lifeless recorded voice on the other end repeated itself into oblivion.

No one else called.

The default response now when you receive a call is to hang up before you answer. A ringing phone once meant possibility or connection; now it only further erodes a sense of shared trust and opportunity. You win, I lose. I win, you lose. I don't want to know you, because if I know you, then I might become worried that my winning is causing your losing, and I don't want to know or care - or rather I can't.

The unknown is dangerous. A gun in a backpack. A suicide bomber in a burqa. An abuser in a collar. A rage behind the wheel.

How can you build trust when online you can be anybody?

So we roll, from narrative to narrative: salvation in a shoe sale, security in investment, closeness in the artificial, a filtered existence, a filtered set of stories to fit my tiny pinprick of a worldview.

A quid pro quo - no quid pro quo. Even Latin fails to fill in the gaps of a society that claims to be Christian but insists only on doing that for which it will be repaid. Jesus, of course, gave everything in return for nothing - but I do not know the Latin for that, perhaps the closest is expiatio or caritas, which has become a dirty American word.

In searching for a narrative in 2019, a ground on which to set my feet and fall to my knees and pray, one Sunday night I found such narrative in two overlapping books, written by two women who walk daily like you, like me, in the murky undecided, seeking the light shining in the darkness.

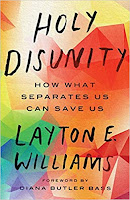

Holy Disunity, by Layton E. Williams

A Southern-born, Georgia and Texas-Educated, Presbyterian liberal queer minister - Layton is a writer friend of mine who I have yet to meet in person (we'll be presenting together in Arkansas at Lyon College in February!).

I've had her book sitting on my end table in the living room for more than a month, its cover with its reds and blues and greens and yellows in sharp-edged relief simultaneously beckoning me and intimidating me. In Red State Christians, I reported on our extreme political and religious divides across America, telling personal and pastoral stories across statistics and national trends, and here was Layton explicating the same ideas and juxtaposing them with elegant and unexpected interpretations of Biblical texts, honed by her own experience in a world that often didn't know what to make of her.

As she once clung stubbornly to an elementary school solo, forcing her voice to sing in front of the class despite the garbled and graceless sounds it made - in Holy Disunity Layton stubbornly clings to a faith and a culture that embraced her and rejected her alternatively. She chooses to walk a middle path that is not the middling moderate but instead one of dynamic and inexplicable love, as she writes on page 1, "... I have felt an overwhelming and irrepressible urge to run into the fire, to dive headfirst into the growing chasm between us all, and do whatever is within my power to repair the breach."

Layton's refusal to agree with political positions that dehumanize her, while at the same time refusing to write off the people and places that hold those positions, puts Layton in a path trod by many revolutionaries and leaders of the faith. Like they were, she faces being delegitimized and ignored, left to walk alone in the flames, knowing that it is in this fire where she is being forged by the God of fire and water, of death and life.

Layton writes what I found to be so undeniably true across America, that what we as people of faith are called to in this moment is not unity but relationship - relationship being the one thing that can bring change, harmony, and peace to a world that has lost its ability to trust one another.

Throughout Holy Disunity I could feel Layton battling, against the church, against the world, at times even against herself - desperate to show that relationships could be forged by disagreement and truth-telling, even when it hurt. I loved reading about her relationship with her conservative Christian mother, who sat in the front pew when Layton finally returned to preach at the church where she grew up, after coming out as bisexual. Her mother's presence in that space, as much as Layton's presence preaching, serves as a bulwark against the shifting sands of distrust and uncertainty that plagues America today. We can still love first.

All Shall Be Well, by Catherine McNiel

Next to Layton's book on my table, in a pile for about the same number of days, lay All Shall be Well, by another writer friend who I have yet to meet in person, Catherine McNiel.

If Layton's cover challenged and intimidated me with its bright colors and sharp edges, Catherine's cover felt like a cool drink of water next to a lapping brook in a clearing in a wood. Her letters, photographed out of carefully arranged soil, were ringed by pinecones and robins eggs and flowers, bees, and sticks. All Shall Be Well.

Do you promise? I wanted to ask her some days.

No way! I wanted to shout on other days.

Occasionally I rested in its refrain, on a fall afternoon when the trees in my front window glowed red, yellow and orange.

All shall be well.

Catherine's book is admittedly different than most of the reading I do ordinarily. I spend my days, by choice, habit and occupation, mired in secular news stories about politics, world events, and human opinions.

As a former sportswriter, I was educated in a writing world dominated by men. I sought to emulate the style if not the personality of Ernest Hemingway, short and unsparing and at times, choppy.

Catherine's book felt like the devotional books I never felt like I was Christian enough to read, not pure enough, not grounded enough. Did I have to drink herbal tea while I read it? Or could I drink a beer?

I soon learned it didn't matter, because Catherine writes not from a place of American Christian-ese, but instead a deeper Christian and even Catholic tradition, hearkening to the mystics and early female church writers who discovered the mystery and even exoticism of God, mirrored in the natural world that forms the foundation of All Shall Be Well.

After reading Catherine's journey from spring to summer to fall to winter, I found myself calling upon her words again and again on days to come, becoming present in the world's rhythms, which continued whether or not the impeachment inquiry climaxed or subsided.

I found myself forcing myself to slow down, to listen, and to give myself permission to be a creature - not striving to be a god myself, controller of every destiny.

Yet do not mistake All Shall Be Well's beauty and patience for quietism.

I found common cause with Catherine as she wrote about the truth of hard-won hope, the hope America is so hungry for today, even if we cannot name it as such - a striving for which we must cling to, that trust that hope will never disappoint us, as Paul promised while in chains.

The hope pointed to in All Shall Be Well is the hope of the cross, not of the gilded crystal steeple or an Oval Office prayer for power.

Read Catherine's words from p. 6-7:

But do not mistake hope for safety. Hope breaks us open. Hope is never naive to suffering, is synonymous not with optimism but with courage. Hope knows with certainty that life overflows with both beauty and pain, and we cannot know which will rise up to meet us. Trembling with possibility, hope sidles up boldly to despair, nestles close, and puts down roots. These two -- hope and despair -- stand always side by side, each determined to outlast the other. If we choose hope, we must join the standoff, with hearts and hands wide open, fighting the urge to fade into despair.

I read these words as a call to action, a truthful call that reminds me of my answer when people ask me if, at the end of my research across red conservative Christian America, did I feel hopeful or discouraged?

I always say that I end with hope, but it is this hope that Catherine describes - a hope won against all odds, a hope won together in the grimiest places, a hope chosen when it seems the most unlikely choice of all.

And so I end here. On a day when I found myself hungry for grounded narrative, I found it in a book about disunity and a devotional about providence. I found it, most importantly, in knowing that the narrative I want to forge and cling to is still being written, and I find it not only in words but in people, like Layton and Catherine.

Comments

Post a Comment